| Loliad R. Kahn by Winifred G. Barton |

CHAPTER 1

TWO YOUTHS IN ATLANTIS

The Rai occupied the dias in the centre of the rostrum; every ear was attuned to the slightest intonation of his voice. At last we were here! in the great city of learning and culture, the centre of the known world, Atlantis!

"Man is a composite being of five fold

strength in a Universe of from

one to seven fold beings, so that in homo

sapiens there is a greater

variety of forces at work than would be found in the

lower orders of

life upon earth.

Of these five forces the first is Ego, that

which Nature first imposes

upon life that it may preserve and propagate itself. A

factor designed

to force living things up the scale of progress.

Second, again of Nature, is the physical mind,

that the body may be

aware of its actions.

Third, the coarse body of spirit, the spirit-aura,

that justice may

come to Nature's product, homo

sapiens, by the absorption into the

spirit-aura of carnal error.

Fourth, the spiritual mind, to give balance

and guidance to the actions

of the body.

Fifth, the astral reflection of the two last

principles, magnetic

force, the source of animation.

Our task is to separate these five components,

examine and analyze the

function of each, then blend them together, each in its

rightful place,

until achieving the perfect whole being..."

The soft tones faded away and the Rai gestured

in dismissal. Zadius,

sitting on my left in the circle of young students,

glanced across. Our

formal initiation was over, it was time for us to consult

the small map

which had been handed to us earlier, showing the way to

our living

quarters.

Having just arrived from Khe, a flat, low

lying land, we were most

impressed by the magnificent panorama of mountains, hills

and valleys

which met our view on leaving the Academy.

The island of Atlantis, which was about two

thousand miles long, looked

green indeed to eyes used only to seeing the sparse

vegetation of Khe,

where sheep and goat raising was the main farming

activity. The

practical Atlanteans utilized their fertile valleys for

their

considerable agricultural enterprises, preferring to

build their homes

and activity centres on the lower slopes of the hills.

This gave a

sweeping view of the countryside to all who gathered

there from

neighbouring lands.

To Zadius and I, it seemed that we had talked

and dreamed of this day

for years ... the day when we would arrive in the

recognized centre of

all culture. Now on arriving, it was strange to find that

our first

impressions were topographical.

Turning to Zadius I commented on the value of

foreknowledge. Having

been born and educated in a flat country, neither of us

had ever

conceived of any other type of terrain. Had we been asked

to describe

our ideas of Atlantis previously, we would have

conjectured upon a

topography similar to that of Khe, but with larger towns,

more people

and an advanced technology.

Perhaps we would have stressed the greater

knowledge of Atlanteans, for

here, in the remnants of the original "Garden of

Eden", the direct

descendants of Adam were living. Although a few of these

people had

spread eastwards and westwards in the course of many

centuries, their

movement was negligible.

On reaching the two roomed house that had been

assigned to us for

personal use throughout our stay in Atlantis, we were

fascinated by the

heatless, shadowless lighting, apparently without source,

and seeming

like daylight, which we later found to be common in all

Atlantean

buildings. One permanently lighted room accommodated all

social

activity. The other was dim and windowless, unless the

long narrow

opening under the eaves of two walls could be termed a

window. This

crack was so narrow that even at the brightest part of

the day there was

barely sufficient light to see the furnishings, which

were no more than

two straw pallets on the floor, each with a single

blanket to cover the

occupant. In Swn, the capital of Khe, our native city, we

had always

slept uncovered on soft downy cushions of silken-like

material, and the

prospect of sleeping on a hard, bumpy mattress that

barely raised the

body from the floor was not inviting. We later became so

accustomed to

Atlantean bedding that we could never again appreciate

the luxury of

Swnian bedding.

Zadius, always the more appreciative of

physical adventure, soon set

off to investigate the mysteries of night life in this

exciting new

city. While I, already a confirmed analyst, sat down to

evaluate a

sudden upset in my academic emotions.

Knowing that in any battle between the will

and the imagination,

imagination always wins, I was distraught at finding how

far astray my

envisioned picture of Atlantis had been -- yet loathe to

admit an

imaginative error. Pinpointing my emotional upset as

being pride left me

fatigued and suddenly homesick for the familiar security

of my native

land. This disruption of logic required adjustment, and

slowly, by firm

repetition of facts, sentimental self-pity was overcome

and mind control

triumphed.

Hours passed before Zadius returned from his

nocturnal revelling. His

first words indicated that he too had suffered from

nostalgia, and that

his prolonged absence had been motivated similarly to

that of a man who

laughs in excess in an endeavour to mask his true

feelings. After an

instant flash of mutual thought transmission, Zadius said.

"At least, Loliad, I forgot for awhile..."

"Perhaps," I replied. "But I

have already conquered, while you have yet

to fight the battle my friend..."

Zadius never forgot this early lesson in

Atlantis, and from it he

gained a more advanced recognition than I, who knew the

theory well

enough but failed to absorb its true meaning.

Many times afterwards I found this to be

abundantly true. People,

quick with advice, fail to recognise a lesson as

applicable to self;

seeing weakness in another and not in my self, I, Loliad,

on my first

day in Atlantis had fallen prey to one of mankind's

greatest failings,

and in so doing became that much less than Zadius, who

respected my

intellectual superiority.

We were now ready to retire, and settling down

on our uncomfortable

pallets in the darkened room, we cheered ourselves with

the pleasant

prospect of three days vacation, a concession granted to

all foreign

students in Atlantis.

At dawn the following day we set forth eagerly to explore the city.

Twentieth Century man, who has always been

accustomed to a monetary

system, will find it hard to understand the perplexity

such a system has

for those born in a country where the word "money"

is not even part of

the vocabulary. The urgent necessity to satisfy our

hunger finally

stimulated the realisation that we were required to pay

for the food we

wanted; although, as we later discovered, we had been

lavishly supplied

by those who had sent us.

As the day wore on we were thrilled by the

sight of beautifully

designed buildings, many of them large and spacious, and

far beyond the

actual requirements of the occupants. We rode the

monorail car systems,

admired the straight wide roads, the canals, and the

underground

gardens. Yet all these sights began to pall as we

remembered that in

Swn, the inhabitants would now be starting their long

hours of prayer

and meditation, and that we had spent a full day with

only a very brief

devotional period in the early dawn to sustain our

spiritual entities.

We discussed this fact with all the fresh

ardour of two young scholars

while walking back to our billet. How easy it had been to

become

distracted by the spectacular; how strange that

Atlanteans, who by all

standards had a civilization far advanced to that of the

Swnians,

appeared to find less time for devotion than our own

people, and how

phenomenal to find that here in the centre of

theochristic activity,

the people seemed to spend less time in practising, and

such lengthy

periods in study -- a situation quite the reverse of

Swnian habits.

Analyzing the illogic of this procedure

occupied most of the night, and

for the next two days we were content to spend the

greater part of our

time re-affirming our intention to guard against this

habit. We would

make sure that we spent equal time in theory and

practise; for what use

is all knowledge unless applied?

On the morning of the fourth day we were eager

to begin the first

course in the two year training schedule designed to

equip us to become

teachers among our own people when we returned to our

homeland.

Whereas today Science is the study of Nature,

philosophy is the search

for wisdom based on the sum total of the knowledge of the

ages, and

religion is an attitude towards Deity: In my lifetime

this combined

learning was taught at the Metaphysical Academy, the

members being

students of Spirit and Nature. The technological and

mechanical sciences

were taught at a completely separate institute.

From earliest childhood my interest had lay in

those things of nature

that were about me. This avenue of exploration led me to

seek an

understanding of cause and effect ... though without

realising its full

import.

Nature study can do naught else but cause the

mind to wander into the

realms of occult mystery, and in my time the formal

answers were to be

found in Atlantis.

To impart the metaphysical wisdom necessary

for quickening evolutionary

processes in humanity, requires the use of the physical

forebrain ... as

will be readily seen in forthcoming chapters.

There is need to speak of the past in order to

clarify why I am what I

am, and how it is possible for mankind to live more

happily in the

knowledge of both worlds -- yours and mine.

For name "Loliad" will suffice. I

was born over seven thousand years

ago to parents who lived in modest circumstances, and who

were of a

class known as "Teachers".

Swn, or Suerne if you prefer the phonetic

version, now forms part of

the bed of the Mediterranean sea, though the catastrophic

events which

caused its final downfall did not occur until several

generations after

my demise.

Many thousands of years before my lifetime, a

vagrant planet had passed

close enough to our own that Earth's axial motion was

affected. This

caused such tremendous upheaval that areas that once had

been of

tropical climate became covered with ice. The melting of

this ice,

combined with the heaving and shifting of the land

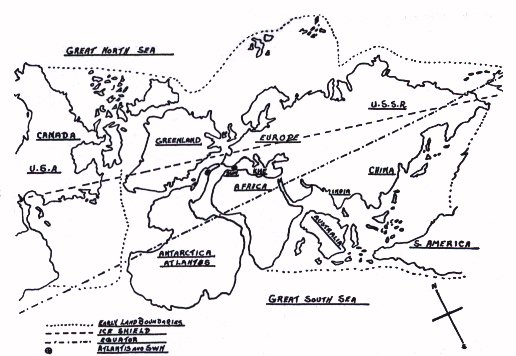

masses, left Earth

looking much like the illustration below with Atlantis as

an integral

part of the Earth's land mass. The Americas were joined

across the

Pacific to Russia, Japan, China and Africa etc.

Civilization was centred

in the areas now called the Mediterranean.

There were two oceans -- The Great North and

the Great South Sea. The

British Isles, Europe, Iceland, Greenland, Russia and

North America were

joined to form the shores of the Great North Sea, though

North America

extended much farther west, so that the Grand Banks were

the eastern

limits. Large lakes formed much of the hinterland of the

North Americas

and only the southern regions were fertile.

Suerne was the large central city in the land

of Khe, a vast prairie

country bordered almost completely by mountain ranges.

These kept the

population from dispersing and formed an effective

barrier against

would-be invaders. The western border of Khe was

approximately five

hundred miles east and slightly to the north of Atlantis

City.

Suernians lived on a tribal basis, drawing all

required supplies from

central storehouses. There was plenty for all.

Distribution was on a

per capita basis regardless of occupation. There was no

such thing as

wealth or poverty.

A white cotton robe was the common dress of

all people, both male and

female, with a loose over-robe of varying colours which

denoted the

occupation of the wearer (green in my father's case).

Elders of the

tribe and those to whom special honour was due, wore a

distinctive sash

and certain items of head-dress to indicate their status

and degree of

authority.

While social law permitted certain men to

remain single, there was no

such thing as an unattached woman, and most men had from

two to five

wives.

My mother loved her children dearly, and all

children for themselves.

She rejoiced anew with each pregnancy, and being

extremely wise,

realised that her deportment at this time would have

considerable

bearing on the future life of each child she carried.

Though well versed

in the household arts, Mother, as was the custom with

women, had little

formal education. Each evening she spent many happy hours

learning

from my father as he discussed his knowledge with the

family. I was the

culmination of two previous birth experiments in which

Mother forced

her thoughts into certain preconceived channels, and the

ultimate results

amply proved the wisdom of one who recognised the

tremendous responsibility

of bringing new life into the world.

Family life in Suerne was quite unlike that of

the Twentieth Century.

The small children of the community were considered the

responsibility

of all adults. During games, should any adult notice one

small

individual being overly aggressive, it was the observer's

task to talk

to the child, explaining this misdemeanour. It would be

considered

ludicrous today to see a stranger delivering a lengthy

lecture to

youngsters playing on the street.

It might seem even more peculiar today to

observe children, barely able

to master a few words, listening to lengthy discourses by

their elders

on the facts of life. Yet in Suerne it was realised that

education,

begun in the womb, should be carried into the very

earliest days of

childhood experiences.

At a very tender age, Suernian children were

separated from their

parents, and put into groups in keeping with their mental

potential. And

while being permitted to visit their parents, the

children then fell

within the full jurisdiction of the teachers. From this

time forward

the children lived at school among others of their own

age, sleeping in

the same compound, eating and studying together. They

were separated in

later years, the boys according to their prospective

professions, the

girls returning to their parents homes at the age of ten,

to give their

full attention to the domestic arts, as at this time

their formal

education was ended.

After one year of intensive study a Suernian

child was considered to

be a teacher by the very simple reasoning that this child

was possessed

of knowledge unknown to a younger child. Thus children

were taught to

teach, and in so doing exercised their own knowledge,

forcing the brain

to use and repeat that which it had learned.

Many hours were occupied with silent sitting

as each new piece of

information was digested and correlated with earlier

lessons. All

instruction was verbal and had to be remembered in detail.

The class sat

cross-legged in semi-circles around the teacher,

absorbing his every

word.

At the age of five, in keeping with the custom

of my people, I was

brought before the Tribunal of Learning where oral

examination brought

to light an intellect already stimulated with burning

curiosity, and at

this time my future life's program was mapped out by the

elders with my

faltering concurrence.

It is of interest to note that through the

Tribunal habitually asked

leading questions in their examinations, the members did

not lean upon

the verbal replies as a basis for forming an opinion of

the candidate.

Although it was not until years later I learned that

these questions

were designed to stimulate thought, and it was by reading

the thought

waves activated by simple queries, which often reflected

quite different

reactions to the stumbling words that ensued, that the

final decisions

were made. At the time of this examination I had already

spent two years

in the primary class designated by the first school board.

After three years of further instruction the

selective groups were

again subdivided, my small class being moved to more

secluded quarters,

which threw the children into very close companionship.

It was here

that I first met Zadius.

The intensity of our studies precluded most

forms of recreation or

sports, and even when a rare game was permitted it was

designed to

further educate though encouraging a competitive spirit.

It was a rare

occasion indeed when I met my family for more than a

brief word in

passing, and which so much still to learn the thought of

returning home

for a holiday seemed entirely impracticable.

As these childhood years sped by my insatiable

thirst for knowledge

grew and would have developed into an uncontrolled

passion but for two

saving features; firstly the wise counselling of my

teachers; and

secondly -- Zadius...

The accent of teaching in Suerne was always

placed upon the class, the

country, and the evolution of humanity as a whole. Close

personal

friendships were discouraged. But despite all training to

the contrary,

the life-long friendship between Zadius and myself

blossomed from our

first acquaintance.

Our personalities were poles apart, but

Zadius' gay and often frivolous

inclinations complimented my own sternly studious outlook.

In

retrospect it seems almost certain that had this

companionship not

developed, I would never have become aware of the lighter

side of life

-- to the detriment of my work on Earth and in heaven;

while Zadius was

undoubtedly prevented from getting into mischief at a

time when study

was essential to his welfare.

During our Atlanteans sojourn Zadius displayed

his natural capacity for

gravitating to just the right places where the maximum of

enjoyment

could be found for two young men weary from long hours of

intensive

study. Not that I wish to be misleading by insinuating

that I was in any

way a reluctant participant -- far from it! It was simply

that Zadius

and I each recognized the field in which the other was

best equipped to

lead, an arrangement which proved to be of lasting mutual

satisfaction.

To win the Atlantean Scholarships was the goal

of every lad in Khe.

Daydreaming of even the remote possibility of such an

event had sped

many of our leisure moments for years before.

Even so, when in our fifteenth year, Zadius

and I actually heard that

we were the successful candidates it seemed hardly

credible. Our joy

knew no bounds, for it had long been reiterated by our

teachers that the

Atlantean Academy of Metaphysics and Institute of

Technology, together

housed the intelligentsia of the known world. Before

graduating from the

former, a student would have advanced into the realms of

understanding

where the aura could be separated from the tissue during

deepest

meditation, to roam the Universe, or wander to every

corner of the

earth. Though this task took two years or a lifetime of

concentration,

for a willing student, no less could be accomplished, and

on completion

of the courses a graduate would return to his homeland to

become an

instructor in the Metaphysical Arts and Sciences.

There was one other choice for a few selected

graduates, that of

remaining in Atlantis for his lifetime (with brief trips

home for

post-graduate lecturing) in order to attain the ultimate

goal of

complete knowledge of life, death, and life thereafter;

which, as it

happened, was the path of my choosing.